Estimating the Value of PIDs

The PID-Optimized Research Life Cycle

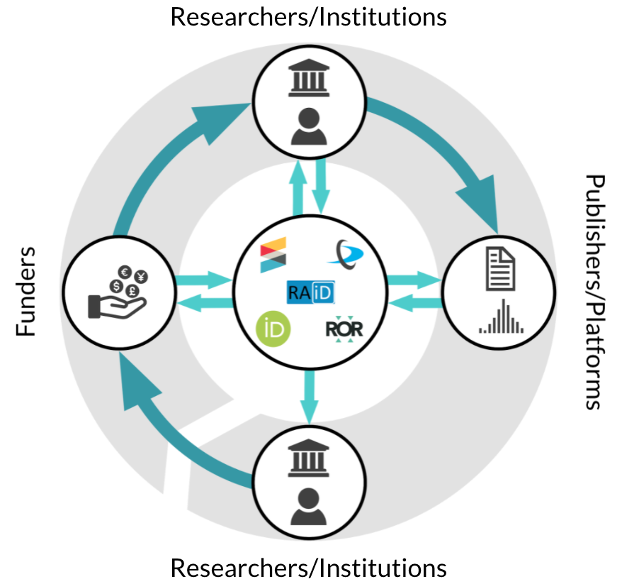

Persistent identifiers (PIDs) are increasingly being used in the research ecosystem and beyond; for example, EIDR identifiers for movies and TV shows. They’re valued not just because they enable unique identification of a person, place, or thing but also because of the metadata associated with them. By making connections between various entities, the information contained in this metadata can then be shared within and between systems. And, because those connections are made using PIDs, they can be trusted. This makes it possible to reliably associate a researcher with their institution, their funders and grants, and their publications and other outputs, for example. PIDs are, therefore, an important element in many information standards and recommended practices, including metadata schema like Dublin Core and JATS.

But, while we can all agree that PIDs are valuable, determining exactly how valuable they are is more of a challenge. In theory, as described above, they make information flow more accurate and efficient—but how can that actually be measured? And, given that there is also a cost to integrating PIDs, for example, in manuscript submission systems, grant application systems, research information management systems, and more, how can you be sure of getting a good return on the investment you make in implementing them—both in terms of technology and outreach?

In recent years, a number of studies have attempted to quantify the benefits of PIDs, the latest of which is a cost-benefit analysis for the UK. This study, commissioned by Jisc as part of their national PID roadmap project, was carried out by MoreBrains Consulting Cooperative with additional financial analysis by Paul Clayton. Earlier work on the project identified five priority PIDs—Crossref and DataCite DOIs for outputs, ORCID IDs for researchers, Crossref DOIs for grants, ROR IDs for organizations, and RAiDs for projects—and recommended the creation of a UK PID consortium to increase their adoption. The report found that, if the consortium could meet adoption targets for these five PIDs of 67% by year 3 and 85% by year 5, there would be an estimated cost savings of £5.67 million over the course of five years (taking into account the cost of setting up and running the consortium itself). It also identified a number of other less-tangible benefits of a consortial approach, including greater influence with vendors, consistency of approach, portability of metadata and workflows, increased ease of collaboration, and a leveling of the playing field between different types of institutions.

The cost-benefit analysis considered three different approaches:

- Status quo—no improvements to the current research information system

- Institutional improvements—implementing a series of PID and workflow integrations at the institutional level

- Consortium-coordinated support—covering all UK higher education institutions

The costs of setting up and running the consortium were based on actual costs of the existing UK DataCite consortium (run by the British Library) and ORCID consortium (run by Jisc). Implementation costs were extrapolated from the known cost of integrating for an institution.

In terms of benefits, three broad areas were identified—metadata exchange/reuse, automation of processes, and improved business insight and analysis. The cost-benefit analysis focused only on the first of these, because it is the easiest to measure. It used the most conservative estimate of metadata exchange, assuming just one reuse, even though metadata is actually reused much more than this. The financial and other benefits of increased PID usage would, therefore, only increase when more realistic estimates of metadata use, as well as better automation and analytics, are factored in. Likewise, the analysis primarily focuses on benefits for the higher education sector, although there would clearly be gains for funders and publishers, too.

There are some notes of caution in the report. For example, a consortial approach could benefit larger research-intensive institutions over smaller and/or more specialist ones. However, since everyone will benefit even more if there’s the widest possible buy-in and participation, there’s a strong incentive to ensure that those smaller institutions are fully engaged. And, of course, the proposed consortium would provide them with exactly the sort of technical and communications support they would find hard to resource themselves.

The infographic shown above demonstrates what the sort of fully PID-optimized world envisioned in the cost-benefit analysis would like. It’s a world where persistent identifiers are registered, used, and shared at all points in the research lifecycle—by funders, institutions, publishers, and of course researchers—at the earliest possible point in the process, in order to derive the maximum possible benefit.

Although the analysis is focused on the UK higher education sector, the hope is that it will provide a good model for further analyses in other countries and communities. As well as the analysis itself, the UK PID Consortium Cost-Benefit Analysis report also includes a brief review of some of the earlier PID analyses, several case studies, and an Excel model that can be used to estimate cost savings for individual institutions, based on their own data.